This Substack is about life in Viêt Nam from the viewpoint of a 10-year expat who spent his first 60 years in a low-context culture.

One of the great things about visiting or living in a country other than the one whose passport you hold is that it’s different. It may be a little different (e.g. money, weather, clothing styles) or completely different (e.g. language, the side of the road they drive on, religion(s), culture, etc.). The reason we travel is that it takes us to places NOT like home. Many people never get a passport because they are just-fine-thank-you with where they live and don’t feel the need to or don’t want to experience ‘different’. But not us.

In the 40+ years since I got my first passport, I’ve been to 29 countries and have found ways to embarrass myself in a good number of them. The funniest of those were language-related, others were cultural mishaps.

We travel knowing the language will almost always be different, even when it has the same name, but how many of us think ahead to the deep cultural differences?

Most of us can travel within our own home country and find cultural differences—even in Singapore, which is so small it’s both a country and a city. Culture comes from language, shared history, values, customs, and people. If it varies within countries, how could someone expect it to be the same across a border as it is in their home country? Yet they do.

Every week there are posts in the local Facebook groups in my small city (~200,000 people) in which both tourists and expats complain that things are different here compared to their home country.

Well, DUH!

Some even ask a version of

Why can’t they do things the right way?

My answer, mostly to myself these days ‘cause I grew tired of repeating myself, is always the same:

“They do what works for them. THIS IS NOT YOUR HOME COUNTRY!

”If it were, you wouldn’t be here.”

Sometimes I add the part most people wouldn’t:

It is better to remain silent at the risk of being thought a fool,

than to talk and remove all doubt of it. — (~Maurice Switzer)

Since you’ve read this far, I’m going to figure that you realize the culture will be different and that you are actually looking forward to that part. Great!

But…

Since this series is written with the thought of helping current and future expats, I must warn you that some of the cultural differences we celebrate as travelers can wear on us as we become expats. What was once novel and interesting can, over time, become a PITA.

Vietnamese Culture

Additionally, there are many things that don’t register as a challenge during a short (less than three months) visit. This can be because they are still ‘unique experiences’ or because either we don’t encounter them or they don’t register with us until we’re deeply embedded in our adopted society.

This is why, when someone tells me that they love it here and would love to live here full time, my reply is

Come here for a minimum of six months; rent a room or apartment among the natives; learn some of the language (numbers and money first to ease your interactions with shopkeepers and restaurants); and eat the local foods. Do all of these things as far from people from your part of the world or who look like you as you can. You’re still going to be surprised later, but less so.

Then, if you still love it, go home; sell everything you can’t bring or buy here; and buy a one-way ticket back. Burn your escape route so you don’t wimp out. If it doesn’t work out here, there’s a whole world of other possibilities, one of which will work for you. Instead of giving up and going home, try another one.

What, you may be wondering, could be so upsetting/deal-breaking that it would take six months to figure it out? Lotsa things, all depending on who you are and what gets under your skin. It also depends on how long it takes you to realize that no matter how much you whinge about it, it’s NOT going to change, so you’d best chill.

The best advice I can give to a potential expat anywhere is to read up on high context vs. low context cultures BEFORE making your decision. I wish I’d known of this prior to moving here, and am happy I know it now. I first heard of high and low context while waiting for a Covid-era conference call to start. One of the other participants asked how I like living here and part of my reply was that I “get in trouble” multiple times every month for ‘saying’ things I didn’t say. She told me it’s because my first 60 years were in a low context culture and I now live in a high context culture. As soon as I got off the call I hit up my preferred search engine (DuckDuckGo) and did some reading.

From this web page:

For low context cultures, the exact meaning of words is important, in comparison to high context cultures which put the focus not just on what people say, but when, where, and how they say it, and even what they do not say at all. A lot of meaning is implicit, while the social setting and personal impressions play an important role in building trust and understanding. To put it simply, people from high context cultures tend to leave some things unsaid, while people from low context cultures are quite direct and mean what they say as they said it.

For years, I’ve said that the way they communicate here in Vietnam is what we from low context cultures (US, UK, Australia, etc.) would call passive aggressive; they NEVER go right at something and gods-forbid anyone ever says exactly what they mean. I, on the other hand, have reminded my wife >1000 times (no exaggeration) that I mean ONLY what my words say; there is no hidden message.

For example, when my daughter was five or six, right after a couple of her second cousins left, she discovered that one of her favorite stuffed animals was missing. She was quite upset, so I suggested that my wife call their mom and ask if the cousins had seen where my daughter had put it.

From my wife’s reaction, you would’ve thought I called their mom a whore. According to her, even mentioning that something went missing during a child’s visit is saying that the child stole it AND the parents are horrible people who raised a horrible child.

I was blown away, and it wasn’t the last time.

That was more than six years ago and about four years before I learned why. Although I’m getting better, I still put my foot in it at least a couple times a month, and that’s with me taking a few beats before I open my mouth in an attempt to simulate passive-aggressive communication. It’s exhausting.

I wish I’d earlier remembered the joke going around back in the 90’s when I worked for a Japanese automobile manufacturer:

How does a Japanese businessman tell you to go screw yourself?

“Interesting… Let me get back to you on that.”

There’s also a really good book on the subject that I read at about the same time and completely forgot when I moved here that it can also apply to personal relationships:

Riding/Driving Culture

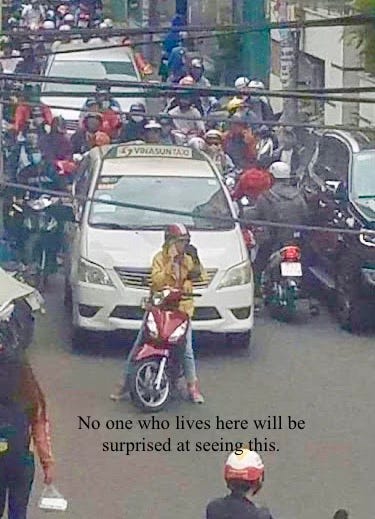

Another of the big cultural differences for me is how different the culture of driving/motorbike riding is from the traffic laws. Vietnam has traffic laws similar to those in other countries, but the riding/driving culture pretty much ignores them.

When I came here as a traveler, and even for the first couple years I lived here and rode every day, it was a novelty. I just went with the flow. That’s actually one of the secrets to riding in a big city—be one of the fish that makes up the school,

not the minnow who thinks they’re a whale.

Then the novelty wore off and I started to think “they have laws and they should follow them.” Somehow, the smaller the “school”, the more it bothers me that everyone’s out for themselves and the rest of the world can go screw! That, of course, is MY problem; it’s certainly not going to change.

A few years after moving here I wrote a seven-part series for my still-there-but-inactive blog on what it’s like to ride here, with a heavy emphasis on wearing a proper helmet so you don’t have to re-learn the alphabet. Part 4 is on the motorbike culture. Most of it is applicable to driving cars, too, though I strongly recommend NOT driving a car here unless you’ve been here more than a couple years.

I’ve included some of the questions from Part 4 to give you a feel for Vietnam’s (and Southeast Asia’s) motorbike culture:

How would you fare riding a motorbike in Vietnam? Take this simple quiz to learn how much you know about the riding culture. Choose the best answer:

2) When turning left, you turn from

a) Your left lane to the new street's left lane

b) Your left lane to the new street's right lane

c) Your right lane to the new street's right lane

d) Either b) or c) depending on your mood

4) The lines on the road are there

a) To let you know which lane is yours

b) To mark the center of the road

c) To indicate whether or not it may be safe to pass another vehicle

d) Because they have them in other countries

6) When your friend has had too much to drink, you should

a) Take away their keys.

b) Put them in a taxi or take them home yourself.

c) Help them balance on their motorbike until they get some momentum going.

d) Call their spouse.

10) The maximum allowable speed is

a) Dependent on road & weather conditions

b) 40 kph within city limits; 60 kph outside

c) As posted

d) Whatever I decide it is

18) Most locals ride as if

a) There is no one else on the road

b) Either their hair is on fire or going over 10 kph will kill them

c) Whatever is behind their front axle does not exist

d) All of the above20) When making a u-turn, you

a) Pull over to the right and wait until there is a break in traffic.

b) Wait until the next roundabout or large intersection.

c) U-turns are not allowed within city limits.

d) Just go for it wherever the urge hits; everyone can wait as you block traffic.22) Riding on the sidewalk is permissible

a) Never

b) Only if there are no pedestrians within 50 meters

c) Only during daylight hours

d) Whenever you want; no one matters but you

Let’s see how you did…The answer to 6 is c)

The best answer to all the others is... d)

None of these is hyperbole. I see all of them except 6) every day; 6) happens mostly at night.

That’s fine, you may think, I will never ride a motorbike or drive a car there — the choice of at least 10% of expats — so these won’t show up on my radar. Fair point.

But WAIT, there’s more!

How ‘bout a culture in which people of all ages and sexes freely nose-pick and then admire the results in public? These same people wouldn’t think of letting anyone see a toothpick touch their teeth, so they cover that digging with their free hand.

What’s your take on a culture that thinks silence is sadness and LOUD is happiness? Yes, “turn it up to 11” isn’t needed here because it’s always already at 14. If Vietnam is on your list of potential expat destinations and you don’t have hearing aids to turn off, do your due diligence before signing for more than two consecutive nights of lodging. Most hotels are relatively sound-proofed, while most private residences/apartments are not. Our bespoke home is a rarity with both in-wall insulation and double-pane doors/windows, but with everything closed up tight, we can still hear karaoke from 80 meters away.

That’s another one… karaoke. If you like it, Vietnam is heaven. If you hate it, consider picking another country, ‘cause it’s Vietnam’s national pastime. Even people who live six-to-a-single-room find enough money for a BIG karaoke speaker and the culture says you have to open all the doors and windows to allow everyone within 200m (650ft) to enjoy your crooning. This video is from a wedding party, but it all sounds about the same. And yes, she’s holding a table centerpiece arrangement.

Returning for a moment to question six in the above quiz, the culture here thinks nothing of two people sharing an entire 24-can case of beer while maybe consuming a bit of food. Most restaurants will open a case, put it next to the table, and then count the number of unopened cans (always a single digit) to determine the bill before they pour the patrons onto their motorbikes.

It only took one attempted intervention on my part to teach me that this is one of the times it’s better to stay out of other people’s business. Also, wait for a while before you leave so you don’t encounter them on the road.

We travel for the adventures. Enjoy yours soon — the other side of the grass is forever.

Also know that as you stay longer, your definition of ‘adventure’ will probably change.

Especially if you decide to go all-in and marry into the culture.